To mark Lougher Contemporary’s 10-year anniversary, our team sat down with founder and managing director Huw Lougher for an in-depth interview exploring the evolution of the gallery, the realities of the art market, and the lessons learned from a decade of building a globally recognised art business.

Huw shares candid insights on success, strategy, risk, collecting, and what he believes the future of contemporary art dealing looks like.

What did you think “success” looked like when you started, and what does it mean to you now?

Honestly? In 2015, I thought success was being able to juggle starting a new business, a young family and a full time job. The initial goal was to buy and sell as much as possible, re-invest all profits and build the working capital of the business to a point that I could justify going full time and dedicating my working life to the next stage of growth.

I'm not one to look too far ahead, so what success looked like quickly evolved once I got going. The challenge? Breaking into a niche of the art market that heavily favoured those with deep pockets. A decade later, I've recently realized there's a strong argument that this still hasn't changed!

After nearly a decade running Lougher Contemporary, success looks completely different - it's the collectors who email to say they’re still proud to have that special piece on their wall, that alert that you’ve got another 5-star review, and of course knowing that we are continually moving forward.

Our business has become far more complex - we've evolved from a simple online gallery into something much bigger - but one thing hasn't changed: everyone who works with us should feel genuinely valued. That's non-negotiable.

What’s the most important decision you made in the past 10 years that shaped where LC is today?

2022. The art market tanked, and everyone advised the same – business owners, clients, even my plumber! Make redundancies, protect your margins, ride it out lean. We kept a close eye on costs but didn’t make any redundancies.

I trusted our long-term strategy and kept the team intact. It was scary - short-term profits took a hammering - but I believed that the knowledge, relationships, and culture we'd built were irreplaceable. You can't just hire that back when the market recovers.

Now, as we're coming out the other side, the team is our most valuable asset. That decision cost me sleep in 2023, but it's what's driving our growth today, and will put us in a strong position as we enter a stronger market in 2026 and beyond.

What's something you're dying to try that would make traditional galleries nervous?

There's something we've been focusing on throughout 2025 that could fundamentally change how we operate - but I'm superstitious about discussing it before it's ready. Ask me again in 2026.

What I can talk about: for those who know me well, they know that I’m fascinated by the psychology of art investment. Most 'art as investment' advice is either snobbish nonsense or get-rich-quick schemes. There's a middle ground - helping serious collectors think strategically about their acquisitions without losing the joy of living with art they love – ultimately this is how I run my business and I’d argue it’s largely unexplored territory.

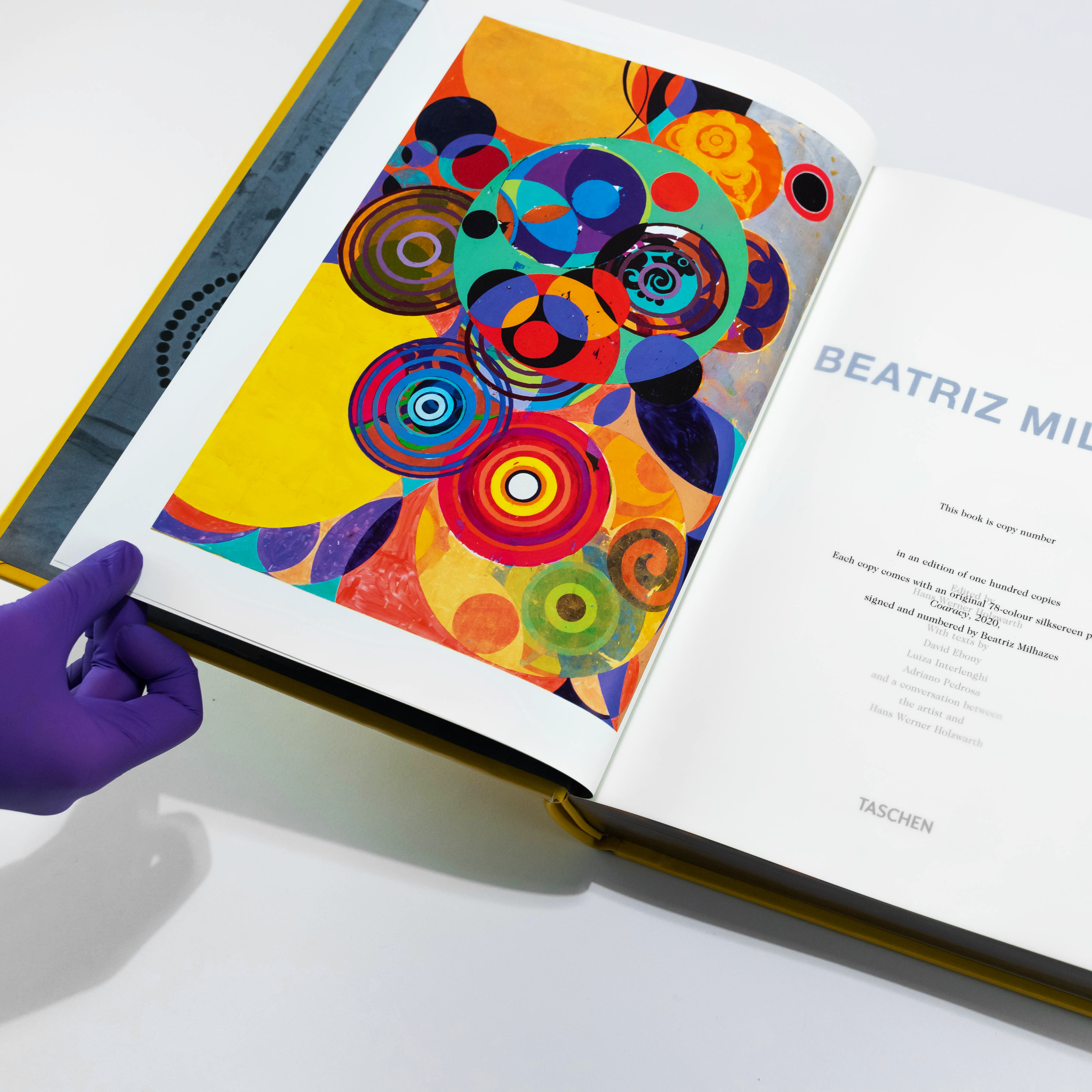

The other experiment? Moving into the higher end of the market. It's risky because we've built our reputation at a different price point, and those collectors have very different expectations. But I think there's room for someone who brings our approach to that level. We'll see if I'm right.

What frustrates you most about how the art world operates?

I love the art market, but certain frustrations have persisted throughout the past decade.

The industry still heavily favours those with capital, making it difficult for new entrants without deep pockets. Primary market access remains gatekept and exclusive, but the bigger issue now is that primary market prices have become unsustainably high - pricing out even well-capitalised buyers.

Operational standards lag behind other industries: poor infrastructure, misleading condition reports, inadequate customer service. Market inefficiencies create unnecessary friction: illiquidity in emerging markets, slow and expensive logistics, dealers brokering works in circles, third-party platforms that don't listen to gallery partners. And authentication remains problematic - fakes persist because the industry hasn't invested seriously in solving the problem.

These aren't reasons to leave the market, but they are reminders that we're decades behind other industries in professionalisation. There's enormous room for improvement, and those who raise standards will win long-term.

If you could do the role of anyone else in the team, who's would it be?

Jo's post-sales role. I'm good at the strategic stuff and the big decisions, but Jo gets to do the part I actually enjoy most - delivering on the service that we promise. She is the first point of contact that confirms the artwork has been delivered.

Of course, it's not all plain sailing. International logistics are increasingly slow and expensive, so she's often managing expectations when shipments are delayed or navigating the rare occasions when something goes wrong (not to mention the decision by President Trump to turn things upside down this year!). She handles the pressure brilliantly - I'd probably lose my mind.

And Hannah's artwork and price research role is a close second - part detective work, part data analysis, all fascinating if you're a market nerd like me.

If you could go back 10 years when you first started the gallery, what advice would you give yourself?

Stop overthinking!

I'm naturally cautious - I like to do things well, not quickly. I like to think that this has served us well in many ways; when we execute, we tend to get it right. But it's also cost us opportunities. I've sat on good ideas for months, perfecting them until the moment passed or someone else moved first. We generate good ideas but we are guilty of over-thinking and slow execution.

The irony? I'm still giving myself this same advice today. Changing how you operate isn't easy - it's an ongoing battle between wanting to be excellent and knowing that sometimes 'good enough now' beats 'perfect later.' I'm getting better at it, but 2015 me needed to hear it even more clearly: trust your judgment and move.

What's your karaoke song?

I don't do karaoke. I'm not great with being the centre of attention, and my singing is a bit like abstract art - it's about expression, not accuracy. Best enjoyed from another room, possibly with the door closed.

Which art fair has been most valuable for LC - and which one do you actually enjoy?

I get bored quickly at art fairs. Three hours in and I'm looking for an exit.

But Art Basel's three locations - Basel, Paris, and Miami - make it worthwhile. It's not just the art (though the quality galleries bring is consistently strong). It's the rituals around them: the morning swim down the Rhine in Basel, my early morning run to the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the beach jog in Miami before the fairs open. The Beyeler in Basel, the Grand Palais in Paris - these settings actually inspire rather than exhaust.

Miami in December is particularly valuable, though I'd be lying if I said escaping UK weather wasn't the real draw. The early timezone means I can work for hours before the fairs open - adjusting to jet lag and sleeping have never been my strengths, so I might as well be productive.

After a few days I need to recharge, but typically I’m ready to do what I do best by the time I’m back in Bristol - and that's rarely wandering art fair aisles. It's the conversations before and after, the relationships built over a mocha, the deals that happen away from the white walls. The fairs are just the excuse to be in the same city and to remove yourself from the detail of the every day, to think bigger, to connect.

Having a passion that turns into a business can be stressful and make that passion less joyful. How do you keep your love of art alive?

The business side - pricing, logistics, client negotiations - can absolutely smother the love if you let it. So I'm deliberate about keeping spaces where art isn't transactional. I'll visit art fairs and exhibitions with no business agenda, just to see work that moves or challenges me. I read art criticism and history outside my market niche. I collect personally - pieces that I'd never stock for the business, work that's not commercially viable but reminds me why I started this in the first place.

The harder part is that running a business really is all-consuming. It follows you on holiday, wakes you up at 3am to bid in an auction, hijacks your thoughts when you should be present with family. That's not unique to art - that's being a business owner and being ambitious. But having genuine passion for the work and for the vision itself makes the obsession sustainable rather than destructive.

Will the passion always be there? I don't know - I've thought about that. For now, though, I still get genuinely excited when we acquire something special or when a collector connects deeply with a piece. That feeling hasn't dulled yet. The day it does, I'll know it's time to reassess. But I'm not expecting that day anytime soon, and I hope, like many in our industry, it never comes.

If you could take an art history class focusing on a 40-year period of time, what class would you take and why?

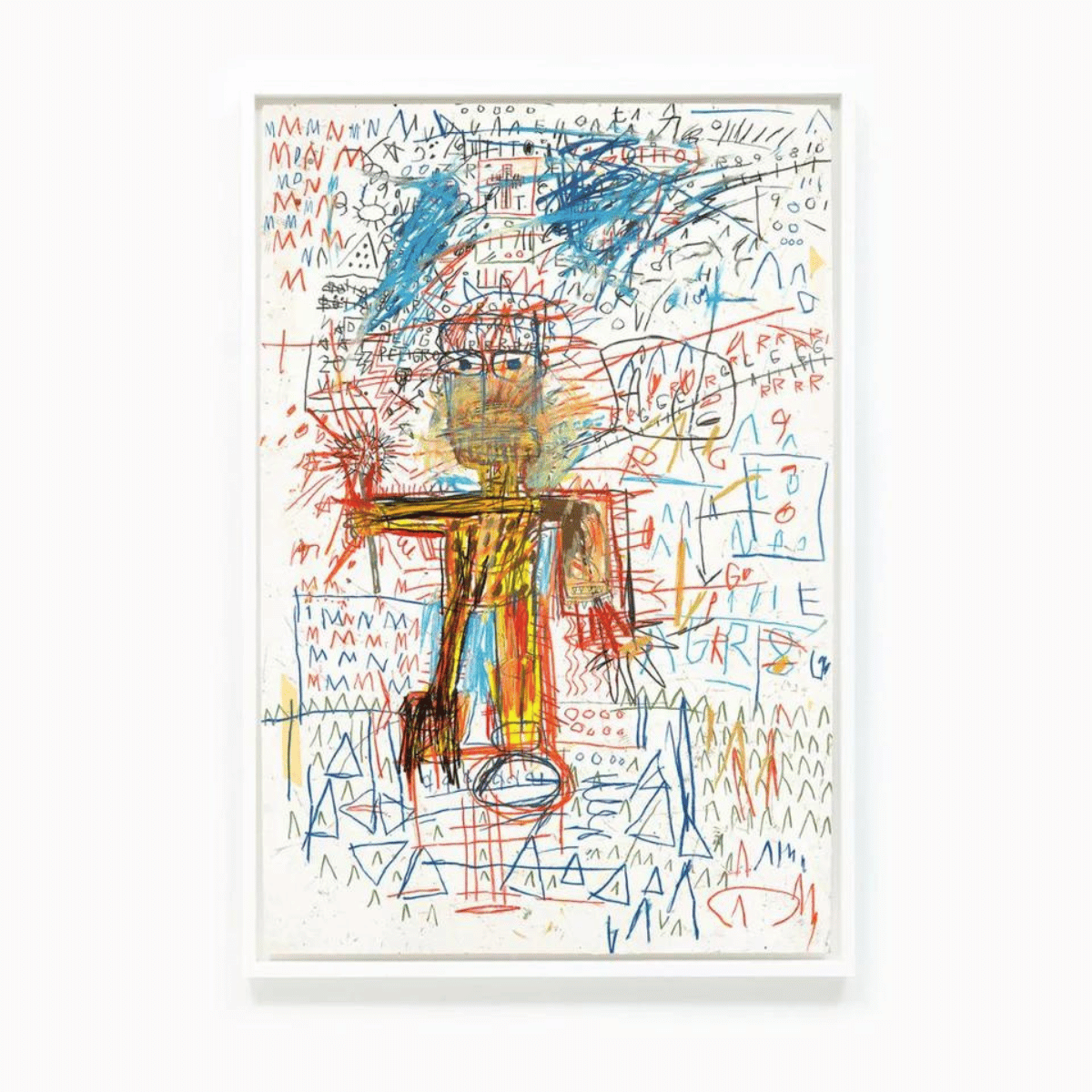

1945 to 1985 - post-war through Abstract Expressionism and into what came after.

I'm an accountant by trade who stumbled into the art world. I’m not an art historian, and whilst I bring commercial expertise that many dealers lack, I've always been conscious of that gap. Abstract Expressionism particularly fascinates me - Rothko, Pollock, de Kooning - there's something about the scale, the emotion, the sheer ambition of it that draws me in.

Those 40 years take you from the birth of Abstract Expressionism through its dominance and decline, into Pop, Minimalism, and Conceptual art. Walking through major museums, that's often the period where I find myself stopping longest, wanting to know more about the context and conversations between artists.

Who is your favourite artist and their best piece of work, in your opinion?

Banksy's and Trolleys (Colour) - the first print I ever bought, and still one of my favourites.

It's his commentary on consumerism wrapped in this absurd, beautiful image: primitive hunters stalking a shopping trolley like it's prey. The ridiculousness of it makes you laugh before the critique sinks in – the ease at which we ‘hunt’ for our food today. We're all hunting for the next purchase, the next acquisition, treating consumption like survival. There's something both funny and deeply uncomfortable about that.

Trolleys is where it all started for me. I had zero interest in art until Banksy - the street pieces, the prints dropping on Pictures on Walls, the exhibitions. It gave me something to chase, to collect, and it was exciting and fun! That print launched an obsession that eventually became a business.

The irony is that whilst Banksy triggered my passion for art, I deliberately didn't build LC around him. The Banksy market is oversaturated, and focusing on one artist felt limiting. I wanted to offer clients more range. But I'll always be grateful to Trolleys for being my gateway into this world - even if the irony of building a business around buying and selling art, after falling for a piece critiquing consumerism, isn't lost on me.

What keeps a gallery moving forward? The art? The people? The clients?

The people. You can have museum-quality art and deep-pocketed clients, but without a team who give a damn, it all falls apart. The art attracts clients, the clients fund growth, but the people make it sustainable. Everything else is ultimately replaceable - a good team isn't.

What is your biggest sell out?

Getting caught up in speculation during 2021-22 - emerging artists and, naively, NFTs.

I was obsessed with market analysis: tracking auction results, monitoring gallery moves, timing hype cycles for emerging artists. With NFTs it was even worse - Discord channels, mint strategies etc. I convinced myself it was sophisticated research and analysis, but it was just profit-chasing.

The NFT speculation was particularly stupid. I should have trusted my instincts - it all felt hollow - but I got swept up in FOMO and quick-return promises. Worse, it completely side-tracked me from actually growing LC and building real relationships with art and collectors.

Both were pure speculation dressed as expertise, treating art like financial instruments. It contradicted everything I value about thoughtful collecting.

Which artwork in your collection do you regret buying the most and why?

I have quite a few works sitting in storage that I bought for the wrong reasons - pieces I never hung, bought for speculation rather than love.

The risk with emerging art investment is high - you're gambling that the artist's profile will build and values will increase. I'm not against it, but the odds are stacked against you. More often than not, those pieces just sit in storage as expensive reminders that chasing hype is a terrible collecting strategy.

It also taught me why LC focuses on editions by established artists. It's the market I genuinely believe in - better liquidity, more predictable value trajectories, lower risk for collectors who want both enjoyment and investment potential. I learned that lesson the expensive way so I can now help collectors invest in the market segment that actually delivers: established names where you can enjoy the work and see value growth. That's not speculation - that's informed collecting.

If you started Lougher again today, what kind of company would you build?

The same business, but I'd move faster and think bigger from the start (although easier said than done!).

With hindsight, I would have set the business up for growth and expansion earlier. I'd invest in our systems earlier (less spreadsheets, more databases with systems that integrate), I’d expand into higher price points more aggressively. I spent too long being cautious and perfecting things that didn't need perfecting. Conservative by nature, but that cost us growth opportunities.

My finance background means I'm constantly aware that traditional galleries have no clear exit strategy and are difficult to scale. If I were purely logical, I'd be building art market tech infrastructure - specifically operational systems that most galleries desperately need. Better inventory management, integrated CRM, automated authentication tracking, transparent pricing databases. Other industries solved these problems decades ago. The opportunity is significant.

But I wouldn't actually do it. I'm a trader at heart - I love buying and selling. The SaaS model with recurring revenues has tempted me during tough periods, but I wouldn't enjoy it nearly as much as what we do at LC.

So if I started again today? Same business model, just bolder and faster. I'd rather regret moving too fast than too slow.

Our 10-Year Anniversary Charity Commitment

As part of celebrating a decade of Lougher Contemporary, we’re proud to support our 10-Year Charity Boost Initiative, dedicating a portion of anniversary-year proceeds to organisations making a meaningful impact.

Learn more about the causes we’re supporting and how you can get involved here.